PHENOMENALITY: *marvelous*

MYTHICITY: *fair*

FRYEAN MYTHOS: *adventure*

CAMPBELLIAN FUNCTION: *cosmological, sociological*

I suppose fans have ROBOCOP to blame for all the SF-adventure films in which whole cities dispense with standing police forces (all before "Defund the Police!") and depend rather on privatized law-enforcement units. To be sure, the original ROBOCOP takes the position that privatized law is not a good choice over police who report to government oversight, so maybe it's not ultimately responsible for dipstick iterations of the concept like the two FUTURE FORCE movies.

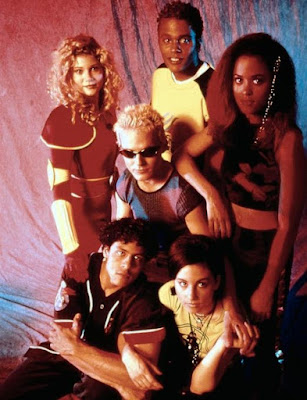

The three CHAMELEON TV-movies are certainly not down in the bottom level of dreck; all three are just decent formula entertainment. United Paramount Network shot a number of these TV-films from 1995 to 2004, and while never outstanding I generally esteemed their best stuff over anything offered by SYFY Channel's original efforts. CHAMELEON was one of a few that was structured as a possible teleseries, though no such series manifested.

In far-off 2028, corporate culture is now served by privatized enforcement agency IBI. Cloning has been perfected, and IBI, seeking to create their own "super-agent," brings forth one of the first adult clones to be genetically crossbred with three species of animals: cougar, falcon and chameleon. Said agent is Kam (Bobbie Phillips), who is supposed to an emotionless enforcer for the IBI, and for her remorseless creator. However, her first mission for IBI puts the company in a bad light: they want to kill off a man who's invented a "credit chip" that allows him to get around billing systems. The IBI does kill the inventor and his wife, but Kam, when tasked with killing the inventor's young son, rebels and flees with him.

Phillips generally strikes a good balance between her training as a martial-arts badass-- she looks very Terminator-esque wearing dark shades and riding a motorcycle-- and her innate humanity, for all that she's a "sub," a "substitute human"-- sometimes abbreviated as "subhuman." There are a few reflections on the morality of making clones to serve as a slave species, but the script doesn't pay a lot of attention to moral issues.

Anyway, despite Kam's prickly nature, she and the kid remain together most of the film, working as de facto partners until Kam finally defeats IBI. Well, actually she defeats a rogue faction headed by her mean creator. Once this faction has been taken down, Kam is free to rejoin a less tainted IBI for future adventures.

Personally, I would have dropped the preposterous "animal DNA" stuff. Maybe I could have bought into her having her muscles enhanced with "cougar DNA," but "chameleon DNA" giving her the power to blend into her surroundings was for me a bridge too far. If the creators just wanted her to be excluded from the normal ranks of humanity, being a test tube baby could have worked as well as the animal-hybrid trope.

CHAMELEON 2: DEATH MATCH shows how the concept probably would have played out in a regular series. This time there are no rogues in the IBI household, but Kam does have to deal with being assigned a new (and unwanted) cop-partner Booker. As the two of them go head to head with a gang-lord named Dulac and his many allies, MATCH shows itself to be much more focused upon crime-fighting action a la DIE HARD. There's one vague suggestion that IBI may still harbor some corrupt elements, but for the most part it's all about stopping the career criminals. The predictable arc of Kam's interaction with Booker-- first they fight, then they protect each other's backs-- is pedestrian and does nothing to advance Kam's perceptions of her own humanity. And although Phillips is still very sexy, the sequel lacks the sex-scenes of the original. Granted, those sequences were rather tame given that they were meant for broadcast television, but they did add some ambivalence as to what duties Kam was trained to perform for her "masters." In place of sex, there are a few more extended kung fu fight scenes.

With the last telefilm, subtitled DARK ANGEL, the creators seemed to go all out, possibly guessing that this would be their last time to breathe life into their chameleonic heroine-- which indeed it was.To be sure, as with the other two films, the script is very spotty on a lot of details-- not only about this future-scape's grand scheme, like how people live in a corporate-dominated culture and how they feel about clones like Kam-- but even the details about how Kam lives her life when she's not out kicking criminal butts. The writers apparently forgot that the original time-frame was 2028, for the prologue shifts the time ahead about ten years, though nothing about Kam's life in the IBI has changed in the least. She does have a slightly more compassionate handler this time out, though he exists only to utter vague misgivings about Kam's temperamental nature, and the possibility that she might be as capable as a wild animal of indiscriminate killing because she's "subhuman." It's not clear why any IBI official cares about indiscriminate killing, if indeed they have no government oversight, but the scene does make the viewer sympathize with Kam over a hierarchy that created her as a living weapon and then hypocritically submits her to psychological review.

Elsewhere in the city, scientist Tess Adkins (Teal Redmann) and her father are working for an energy company, trying to harness "dark matter" as a new source of energy. However, a subordinate scientist and a tough bodyguard named Kane (Alex Kuzelicki) betray the project. They kill Tess's father and carry off the dark matter device, despite Tess's warning that the power of dark matter could unleash a "black hole" capable of destroying all life. The young woman escapes, which doesn't immediately concern the conspirators, until they get the device back to their base, where they find that they can't make the machine work. So they go looking for the scientist, at about the same time Kam is assigned to run the witness to ground.

This basic scenario was already used in the first movie, but this time the stakes are raised in terms of both action and drama. The chameleon-girl finds Tess, but so does Kane-- and in that first martial encounter, Kam realizes that her opponent is also a "subhuman" clone, since he can both fight and heal wounds as well as she can. Moreover, even though he's an adult, Kam recognizes Kane as her clone-brother, though she hasn't seen him since both of them were little kids being raised by a surrogate mother. Again the script drops the ball on a lot of intriguing questions. Was Kane just made from roughly the same hybrid gene-recombination process as Kam, or were they literal brother and sister, albeit nurtured by the nameless surrogate mother? At some point in the past, the IBI simply loses track of Kane. Since he seems to have free will and nothing is said about his having been sold to foreign powers, the best assumption is that he simply decided to go rogue on his own-- though that doesn't really explain why Kam has conveniently forgotten all about him until the time of DARK ANGEL. (Since both of the clone-people wear black attire, maybe "Angels" would have been a better title.)

For all these unquestionable flaws, though, the action is exemplary for a budget-conscious TV-film, boasting four strong fights between Phillips and Kuzelicki and a number of ancillary battles against other lowlifes trying to take Tess prisoner. Kam is consistently shown as being caught between the desire to reconnect with her lost sibling and the necessity to stop his rampage, to say nothing of resenting her own "sub" status. (A memorable line in the prologue conflates her duty "to serve and protect" as being equivalent to a slave's "service.") In contrast to the kid Kam protects in the first flick, Tess doesn't do much to bring out Kam's humanity, given that Tess is just as prickly as her savior for no adequate reason. Still, Kam finally gets a challenge worthy of her talents, not only in her fights with Kane but in her struggle to keep the dark matter from annihilating the world.

Kane, though defeated, escapes, and a coda suggests that Kam may seek to find him again, though he showed no sign of wanting a reconciliation. But even though there would be no more outings for the girl with the animal DNA, at least she went out on a high note.